Most of them even changed their moon. The city lights did not compete with the moon of those hills and infinite plains. Their best bulbs were the stars. After all, Juan Gualberto, María Cristina, Juana Inés and the rest of the alphabetizers went to share the true light: the light of truth.

They were almost children and, at the same time, teachers with much to teach. That campaign devised by Fidel Castro, the Leader of the Cuban Revolution, seemed to all of them a charming madness. No matter their age, the immense challenge, the risks, or the comforts they left at home.

Juan Gualberto Correa tells how he was separated from his family for the first time. «He was studying in high school, in Bahía Honda (then a municipality of Pinar del Río, today in Artemisa). But many others also filled out the forms: we completed three buses. In 1961, the situation was hot. At home they only told me that I could not give up».

After a week of preparation, he arrived with all his energy to a place called Pedrales. The lessons illuminated the lives of six peasants. They opened breaches in the darkness of the place. The young man taught them and, at the same time, he learned to ride horses, helped to sow and pick coffee and malanga.

Correa became accustomed to the dirt floor, to sleeping in a hammock, to the endless chirping of crickets and the coolness of the guano roof. He ate lunch with lots of lard, and rice and beans in the afternoons. He breathed gratitude. The treatment they lavished on him compensated for the insistent nostalgia. When he finished, he left them as a souvenir the lantern that gave him so much light.

Something similar happened to María Cristina Pérez. Her father and mother were very happy with her decision. «I come from a humble family and a rebellious town (Regla), where every night the bombs sounded. My parents fought against Batista’s dictatorship».

He arrived in Güines to teach when he was only 12 years old. She was not afraid to work in the fields or to eat flour. She was so caught by the good that letters do, that she later joined the Makarenko teachers’ plan. Teaching practice led her to Bahia Honda, where she met Correa… and they have been together for five decades now.

They say that there are probably no stories as beautiful as those of the people they taught in 1961. If not the experience of Juana Lorán Abella, who almost drowned in a whirlpool when she was teaching in Sagua de Tánamo, Holguín. Not even if the river itself had come to her house to look for her, would she have convinced her to return, she says. «Dreams are neither abandoned nor sink.»

She had taught reading and writing in Zaza del Medio, Sancti Spíritus, while the roar of bombs and the sound of shrapnel silenced the murmur of waves in Playa Girón. She was also fighting, for the new country project, as part of the Pilot Brigades.

She was almost 10 years old when she started first grade. The rural public school was far away, and her parents would not let her go alone. Then she was already riding a small skinny horse: she would tie it to the front of the school until she finished her classes. So she immediately understood the need to carry knowledge everywhere.

Urgency of letters

According to Leonel Zamora, Master of Science, historian of Bahía Honda, «only primary education was taught there. To receive middle and high school education, those interested had to go to Guanajay and the Institute of Secondary Education in Artemisa. Not to mention the rural area, where classrooms, furniture and the material basis for study were in a deplorable state.

«Children and teachers traveled up to 10 kilometers for a class session. The population census of 1953 recognized that, of the three thousand 660 inhabitants between six and nine years of age, two thousand 284 were illiterate (two thousand 166 resided in the rural zone).

«The same was true of the 22,344 inhabitants aged 10 and over: eight thousand 586 were unable to escape illiteracy; 45.3 percent lived in rural areas.»

Zamora adds that «the children of the poorest stratum of the people could only aspire to the fourth or fifth grade, under the requirement of contributing to the family economy, especially in agricultural work».

He refers to the Alfredo M. Aguayo Public School, made of wood, guano roof, wooden benches and a small classroom, for those who had some resources, since the study material had to be purchased. One group had classes in the morning and the other in the afternoon. Blacks and whites sat in separate rows.

Perhaps it would not be valid to think that Guanajay had a better situation, since it had a Normal School for teachers (high school), the only one in the region. According to historian Reveca Figueredo, the premises and furniture of the public schools qualified as critical.

It was the same in every corner of Artemisa and throughout Cuba in 1958, when less than 90 thousand students had access to secondary school. Most of them could not continue their studies either, much less access university.

Change of scenery

If, then, the country had only 81 high schools, in 2008 the number had grown to 1,941. In just one year of the Revolution in power, some 10,000 new classrooms were built; school enrollment grew to almost 90 percent in the six to 12 year-old age group. Barracks were converted into schools: some 70 former military facilities housed 40,000 students.

And a year after announcing that the country would wage a decisive battle against illiteracy, the new Cuba was shedding that past of ignorance. Next, the largest of the Antilles would also win the battles for the sixth and ninth grades, and embarked on the universalization of higher education.

Children’s circles and special schools, teacher training institutions, universities and research centers, computer and language learning, as well as educational television, multiplied.

Saskia Robaina, a methodologist who works in communications at the Provincial Directorate of Education in Artemisa, illustrates the change well: «Bahía Honda did not have a single high school, but now it has nine secondary schools.

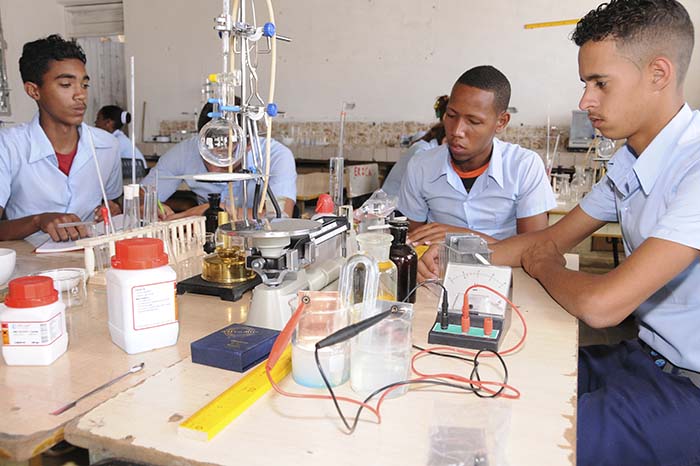

«The lanterns and primers deployed in 1961 gave way to blackboards and computers, agricultural machinery, lathes and laboratories, to learn the secrets of the land, the sugar cane, the sea, the gearing of engines, mathematics, language, history…»

As if that were not enough, the largest of the Antilles contributed to the reduction of illiteracy in several countries, by bringing letters to millions of people, through the programs Yo sí puedo and Yo sí puedo seguir. The light of truth illuminated all of Cuba… and beyond (Joel Mayor Loran, ACN).