One afternoon in 1995, the then deputy editor of the newspaper, Guillermo Cabrera Álvarez, placed on my desk at the Granma newspaper a singular jewel with a carmelite cardboard cover and yellowed paper sheets that the poetics of time had turned into a relic because it was the first biography of José Martí.

The Asturian Manuel Isidro Méndez, a Spaniard of noble lineage, had written the memorable pages of that work, which I later returned with regret, like someone parting with something that belongs to him. Many years after his death, Guillermo still revered old Isidro, recalling his passion, acuity and tenderness for the Hero of Dos Ríos. Every time Guillermo spoke of him, the affection he felt for him was beyond words, and he managed to give those of us who listened to him the same sensation of nostalgia and admiration for his dear friend, to the point that we saw Isidro with the same clarity with which he evoked him, among volumes and revealing stationery.

After reading the book, which I received as a palpable marvel, I meditated on how difficult it must have been for those who knew him or lived closer to his days, the physical death of José Martí, a circumstance that became terrible, dramatically overwhelming afterwards, with the establishment of a republic dependent on the arrogant north that denied then – and denies today – our virtues and integrity as an untamed people. This was a tremendous affront to José Martí, and gave rise to lamentation among the Cuban people, expressions of bitter acceptance of an adverse reality that would not have been so if Martí had lived.

I read in the three-volume Selected Works [Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1992] that the letter-manifesto to the editor of The New York Herald, written in the Cuban manigua on 2 May 1895 and also signed by General-in-Chief Máximo Gómez, was published in Patria, New York, on 3 June of that same year, and by then José Martí was no longer there. I am suffering right now the tremendous impact of those who lived through that sudden and heart-rending absence. In that letter Martí states: «The Cubans recognise the urgent duty imposed on them towards the world by their geographical position and the present hour of universal gestation; and although puerile observers or the vanity of the proud ignore it, they are fully capable, by the vigour of their intelligence and the impetus of their arm, of fulfilling it: and they want to fulfil it».

I am grateful to Isidro Méndez, whom I did not know, for the feeling and the certainty that, in the early days and throughout the neo-colonial republic, there were always illustrious men and honest thinkers who approached the life and work of the Apostle with the respect that a monument like him deserved. The same was not true of the country’s official histories or political life. The American domination and annexationism, neo-colonialism in Cuba, found the vision of Martí as a revolutionary patriot and anti-imperialist, whose thought had undergone a gradual radicalisation, not only in favour of independence but also in favour of social justice, inconvenient and uncomfortable.

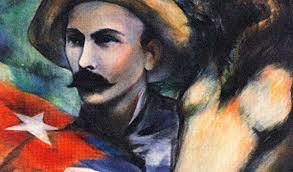

Thus, in a recurrent way – as they still do in the United States – they skewed and distorted the prominent figure of the patriot, presenting him as an unattainable and mythical paradigm, as a romantic idealist with no chance of success except in self-sacrifice, when we know that in addition to being a virtuous humanist, an acute politician and an effective organiser, José Martí was eminently a practical man, with his feet firmly planted on the ground and his strength and soul committed to the end to realisable utopias.

His words of reply to The Manufacturer, reproduced in The Evening Post, would never be invoked: «… But those [Cubans] who have fought in war, and learned in exile; those who have raised, by the labour of hand and mind, a virtuous home in the heart of a hostile people, those who by their recognised merit as scientists and merchants, as businessmen or engineers, as teachers, lawyers, artists, journalists, orators and poets, as men of lively intelligence and uncommon activity, are honoured wherever there has been occasion to display their qualities, and justice to understand them; those who, with their less ready elements, founded a city of laborers where the United States had before but a few hovels on a deserted islet, these, more numerous than the others, do not desire annexation. They do not need it.

The humiliated republic was not Martí’s dream, nor could it open a wide channel for a full, complete, faithful approach to the Master’s work and life. In the cases of the Machado and Batista dictatorships, he was not only denigrated in the very exercise of injustice and crime, but the study of his thought was also considered a crime. Fidel was forbidden to get his hands on Martí’s books: «It seems that the prison censors considered them too subversive, or is it because I said that Martí was the intellectual author of 26 July? I was also prevented from bringing to this trial any reference work on any other subject. It does not matter at all. I carry in my heart the Master’s doctrines and in my thoughts the noble ideas of all the men who have defended the freedom of the peoples», he said in his defence plea in the trial against him for the assault on the Moncada Barracks.

The Cuban Revolution at the decisive hour made possible the independent and free homeland of dignity and justice that our National Hero dreamt of and for which he set out on the campaign trail when he landed at Playitas. The entire revolutionary work is the greatest and definitive vindication of Martí and only in the Revolution has the multitudes been given the luminous possibility of knowing him fully, without fear of revealing all his profound dimensions, of making the branches of that «tree that grows», as his best disciple – the one who carried him in his soul when he went into combat – called him – can unfold widely. (Published in this newspaper in 2002).