In 1953, Santo Trafficante, the Tampa bolitero and, after Meyer Lansky, the most powerful mafia man in Havana, attempted a makeover at the Sans Souci cabaret, which he had just acquired.

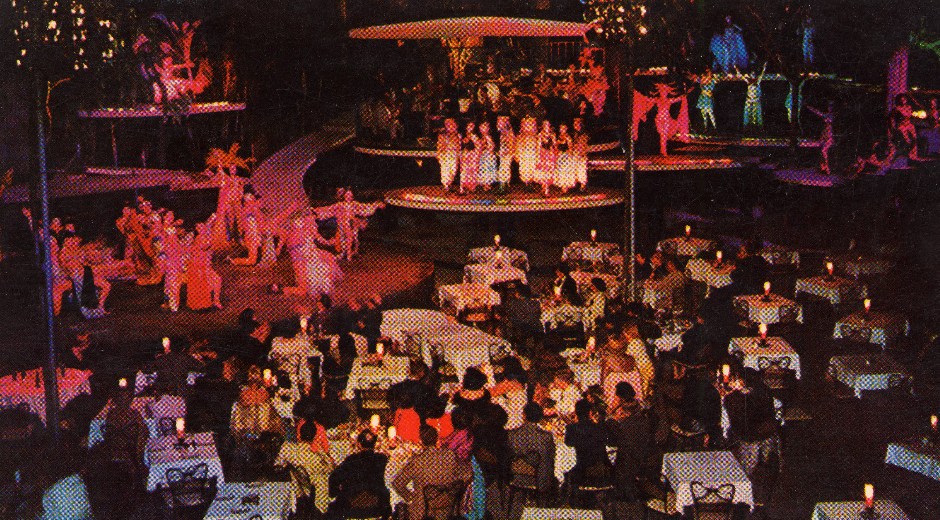

When he reopened it in 1957, he had remodeled the casino and installed new slot machines -the so-called one-armed robbers- and built a hall with a glass roof so that on rainy nights the show usually offered under the open sky could be quietly enjoyed. One thousand one hundred visitors were then able to sit at once in the cabaret areas, which reserved a private space for high rollers who, with no time limit, played against themselves and not against the house, which collected a percentage of the winnings at the end.

It sponsored large choreographic productions and hired important international figures. The minimum consumption went from $3.50 to $5.00, and no additional amount was necessary to access the casino. There was an excellent cuisine and its menu was one of the most complete among nightclubs. The shows included the participation of a 14-voice choir, something unprecedented in establishments of this type. The Nevada Cocktail Lounge offered pleasant musical moments in the casino, independently of the shows outside. Sans Souci seemed to be sparing no resources in its efforts to beat Tropicana. So December 31, 1958 arrived.

The last night

It seemed that the last day of the year would be no different from the others, despite the fact that the Rebel Army was laying an elastic siege around the city of Santiago de Cuba, and Santa Clara was about to fall into the hands of the guerrillas, while Batista’s dictatorship was drowning Havana in a sea of blood.

That night the show Sabor y souvenir de Haití, a production by choreographer Víctor Álvarez, was being presented at Sans Souci, with Martha Jean-Claude, Miriam Barrera, Nancy Álvarez and the dance couple Ana Gloria and Ferrán, while at the Nevada bar the D’Aida quartet was performing.

The show was already over when Meyer Lansky arrived at the facility. He had found out at the Plaza Hotel, while dining, about Batista’s escape and, as he had done in other casinos, he recommended Trafficante to collect all the money and close the place. He told him, “When this town finds out that Batista is gone, we wish we were gone.” Trafficante took out the money, but was slow to close. A short time later an angry mob entered the cabaret.

What happened then? It is not known exactly. Some say the casino and cabaret were totally destroyed. Others claim that this is an exaggeration, that the destruction was centered on the slot machines. Either way, the casino and cabaret closed forever after that night. However, in the page of spectacles of the Havana press the shows of the two initial months of 1959 appear announced. Tangolandia, in January, with Rolando Serie, Nancy Álvarez and Ana Gloria, and Sabor, in February, also with Nancy Álvarez. Were these shows presented there or were they prepaid advertisements that no longer corresponded to reality? It is said that Trafficante never set foot in the place again. The kitchen staff, waiters, bartenders and other saloon employees insisted that the house remain open, but the musicians did not. The motives of both are explicable. The wait staff worked for tips; they had no salary. The musicians did.

As famous as Tropicana

The history of the Sans Souci cabaret seems to have been thrown down the memory hole.

Because of its exclusive atmosphere and refined elegance, Sans Souci became as famous as Tropicana. César Portillo de la Luz, the famous composer of Tú, mi delirio and Contigo en la distancia, who worked as a musician in the bar of that establishment, told this columnist that while Tropicana was preferred by foreigners, Sans Souci was more for Cubans.

Edith Piaf, the Sparrow of Paris, with her raspy voice, got the audience into her pocket when the cabaret’s management thought, after having hired her, that she would not enjoy much acceptance from an audience that, between whiskeys and boiling hips, had little more pretensions than to have a good time and have fun.

In addition to Piaf, in the 1957-58 season, which was the season of the cabaret’s reopening, Denis Darcel, Ilona Massey and Cab Calloway, among others, paraded on its dance floor, and for the following season the management intended to hire Marlene Dietrich, Liberace and Susan Hayward as entertainers for its nights.

For a while Roderico Neyra, that mulatto deformed by leprosy, of short stature and mischievous smile, who made famous the pseudonym of Rodney, was in charge of the choreographies of the Sans Souci, marking with them a way of doing and conceiving the show. When, in March 1952 Rodney moved to Tropicana, he was replaced by an artist of the stature of Alberto Alonso, who with Iroko Bamba Bamba won the “biggest and most expensive” show presented in a Havana cabaret. It had 100 participants.

The cabaret’s cast included dancers of the caliber of Sonia Calero and another one who identified herself as Cara Melo, whom critics defined as dance made woman and who personified the spirit of Sans Souci like few others, it is also said. Broadway producers had their eyes on her.

The world of show business

It was in the Nevada bar where Santo Trafficante caught delirium with Tú, mi delirio, the author of that bolero, César Portillo de la Luz, told this columnist. The composer was part of a musical group that also included Frank Domínguez, who entertained the night at the Nevada. Portillo recalled in that interview that whenever the mafia boss came to the bar he would always tell a bartender nicknamed El Guajiro, who later worked at El Mandarín, to ask the group to play that piece for him. Then, as a thank you, he would send them a bottle of champagne or a $100 bill, which the musicians would share equally.

El Chori had no luck at Sans Souci, and the management of the place was not to blame for that. The famous percussionist used to perform in the seedy cabarets of Marianao Beach, on Fifth Avenue, in front of Coney Island, the so-called “fritas”, when he was hired to perform at Sans Souci along with Miguelito Valdés. In addition to the not inconsiderable pay, the nightclub guaranteed the artist the right clothes, a room at the Plaza Hotel and a car with chauffeur. But that spell was short-lived. Chori was not a member of the Musicians Association and that invalidated him to perform in places of that category. If he did not obey they applied the so-called law of the stake; they would beat him at the end of the performances. And Chori returned to El Niche, the cabaret on the beach where they performed at the time, to their cheap rum and carefree music.

As early as 1957 the cabaret offered Rocky Marciano, the undefeated retired world heavyweight boxing champion, $350,000 if he would agree to face Niño Valdés, his former Cuban challenger, on the premises. But Marciano did not accept the proposal.

The fact could give rise to a tasty chronicle. It happened that, during a training session, Niño, intentionally or unintentionally, threw a right hand at the world champion that sent him to the canvas. Needless to say, the Cuban was Marciano’s sparring partner, but he became his challenger. The champion never gave him the fight. He would soon die in an accident while flying his own plane.

In addition to the aforementioned Alberto Alonso’s show, the chronicle mentions Sun Sun Babae, by Rodney, as another of the great shows that took place at the Havana cabaret.

In that staging, a group of black dancers descended from the stage, followed by the spotlights, and approached the table occupied by a blonde girl who could not take her eyes off the half-naked men surrounding her, who attracted and frightened her at the same time. They ended up lifting her from her seat and taking her to the stage, where the young girl was intoxicated by the sound of the drums and the increasingly loud singing, while the audience, hypnotized and confused, did not know if this was part of the show or not. Suddenly, the blonde, maddened, tore off her dress and, covered only by her minimal and provocative underwear, began to dance. Her movements became more and more frenzied and lascivious and the men would lift her up and she would pass from one arm to the other, until in the midst of a crescendo of music, she would come out of her trance, utter a cry of confusion and hurriedly gather her clothes. Still half-naked, she fled the stage and crossed the hall to exit through a back door. At this point the spectators confirm that the blonde girl – actually the American dancer Skippy from New Jersey – is not just another customer, but is included in the production and, surprised in their naivety, they laugh discreetly at first and then applaud wildly.

No worries

Sans Souci took its name from the palace that Frederick II, the Great, had built in Potsdam in 1745. It rivaled the Versailles of the French monarchy, although it was much smaller. This building was for the King of Prussia a place of rest rather than a center of power. Hence its name, which can be translated as “carefree”.

The same idea animated the founders of the Havana Sans Souci. They wanted their clientele’s visit to be free of worries and anxieties in that Spanish-style villa located on the Arroyo Arenas road, with its shows under the stars.

It opened its doors at the end of World War I and Galician Arsenio Mariño, who had been living in Havana since 1914, was one of its original owners. There he met the woman who would become his wife, who, in time, together with her twin sister, would form the duo Las Hermanas Farry (The Farry Sisters). From that union was born the excellent Cuban actress, singer and dancer Yolanda Farr, who plays a small and fleeting role in Memories of Underdevelopment: she is, in that film, the wife of Sergio, the protagonist. Mariño supposedly sold his share in the early 1930s and went to South America with the Farrys.

Old night, bitter night

On December 31, 1933, Colonel Fulgencio Batista wanted to bid farewell to the year in Sans Souci. He was accompanied by Elisa Godínez, his wife, Sergio Carbó, the most popular journalist in Cuba at that time, and his wife Clara Yáñiz, as well as assistants and caregivers. The couples occupied one table and the other, at a prudent distance, the assistants, while the bodyguards, discreet but expectant, were scattered around the room.

Suddenly the inconceivable happened. The great Havana world present did not hide its displeasure as soon as it noticed Batista’s presence. Some left the place in anger. Others, more daring, rebuked the military man face to face, alluding to his humble birth, his peasant ancestry and the color of his skin. They shouted at him, calling him a guajiro and a fucking nigger.

Batista could not believe what was happening. Ashen from the humiliation, he tried to hide behind Carbó, who had also stood up. He was the head of the Army, the most powerful man of the moment and he could not conceive such an affront. The bodyguards, without losing their equanimity, stood on guard, and his right-hand man, a sergeant who also happened to have the last name Batista, put his hand on his pistol. Clara Yáñiz, who was a tough cookie, took on the defense of the offended party. She mentioned mothers and, as she knew many of the people present well, she called them by name with the most sonorous and degrading adjectives.

The management of the cabaret rushed to the scene and went into overdrive to assure that all the consumption would be paid for by the house, but the military man would not stay there a minute longer. Nor would he celebrate the end of the year. Sans Souci had spoiled his New Year’s Eve.