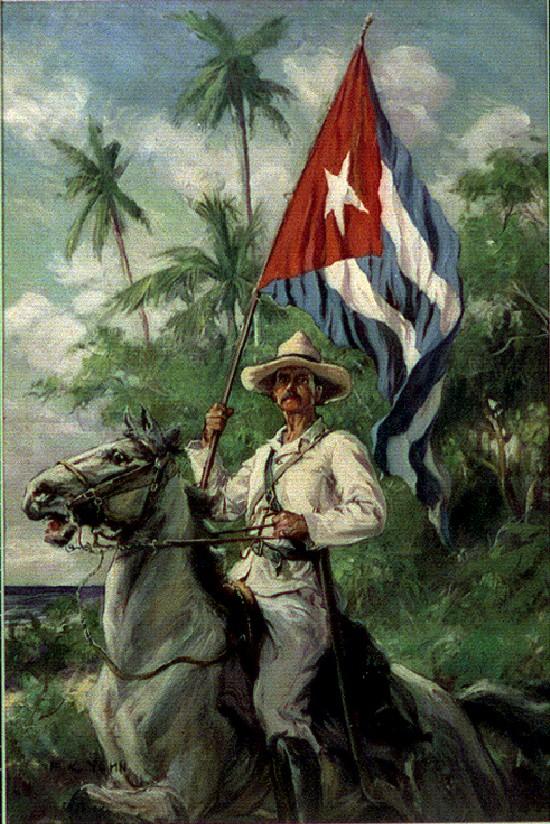

The uprising of 24th February 1895 was not a spontaneous outbreak, but the organised expression of a revolution conceived by José Martí from the people and for the people, with a democratic and military strategy carefully forged.

In 1873, halfway through the course of the Ten Years’ War, José Martí affirmed that in Cuba «the insurrection was a consequence of a revolution.» Thus he explicitly established the conceptual core of the ideological reorientation he imparted to the course of the independence struggle in Cuba. This conceptual core would be embodied – developed as a universal formulation – in the first issue of Patria (14th March 1892), defining the newspaper’s programme: «war is a political procedure.»

The formulation, expressed in the mouthpiece of Martí’s preaching for the necessary war, lies at the centre of the National Hero’s founding thought. As early as 1880, he had shown his awareness that his vision grew in the service of the people of Cuba, and differed from the view held by others, clouded by an «urban and financial way of thinking.» On that same occasion, he established: «The despots ignore that the people, the pained masses, are the true leaders of revolutions.»

Years later, just before its proclamation, on 10th April 1892, the political organisation founded by him to carry out his liberating project would express: «The Cuban Revolutionary Party is the Cuban people.» His democratic conceptions – nourished by the decisive growth of popular forces within Cuba’s patriotic movement – were also reflected in a consistent military strategy, carried even to the manner in which the uprising that would initiate the new war was to be consummated: unlike what had characterised independence movements in our Americas and, within it, in Cuba, the armed struggle would not erupt in an isolated point, but simultaneously, in as many localities as possible with forces mobilised for the feat.

Such strategic orientation obeyed, in the immediate term, the need to maximise the military efficiency of the revolutionary movement, not only against the Spanish Army – which in 1895 would not have to face the continental multitude of forces that had risen against it in the Americas at the beginning of the century – but also against the danger of United States intervention. This danger was, fundamentally, what most worried Martí, as he himself confirmed in his posthumous letter to Manuel Mercado. The complexity of such circumstances explains the determining sense of his eagerness to ensure the war was «brief and swift as lightning.»

At the same time, the advanced and sowing political-military strategy was an embodiment of the democratic character of Martí’s revolutionary project as a whole. As conceived by the Teacher, the insurrection of 24th February 1895 constitutes an antecedent of what we today call the war of all the people. In this, as in so many other cardinal aspects, «he is and will be the eternal guide of our people,» and the intellectual author of our Revolution.

Although circumstances and factors of various kinds prevented all the committed localities from rising up on the 24th of February, several of them did so that day. In Matanzas, where Juan Gualberto Gómez, the Party’s link with the conspirators in Cuba, travelled, the honour corresponded to Ibarra and Jagüey Grande; and in Las Villas to Los Charcones, a focus linked to those from Matanzas.

Armed groups in Oriente – where the plan was most successful – took up arms in at least several places in the jurisdiction of Santiago de Cuba: Alto Songo, El Cobre, San Luis and Loma del Gato, whose village was set on fire; as well as in Manzanillo: Bayate and «almost all the townships of the district,» according to Hortensia Pichardo. Those from Bayamo succeeded in El Mogote, Vega de Piña and San Diego; while Guantanamo forces also did so in Matabajo, La Confianza, the Santa Cecilia sugar mill and Hatibonico, where the enemy Fort was taken. The account of the most important eastern events of 24th February can be concluded with those of Jiguaní and Baire. There Saturnino Lora – according to testimony cited by Hortensia Pichardo herself – expressed to his troops that it «was not a local movement, but a generalised movement throughout the Island.»

Wise words from Lora: although with different degrees of success, all the groups that rose on 24th February acted in fulfilment of the plan conceived by Martí at the head of the Cuban Revolutionary Party. The simultaneity achieved was not the work of chance, but of a carefully elaborated project.

What would become the true pronouncement of that outbreak as a whole, that is, of the necessary war which all the uprisings served as a sacred and founding act, was the Montecristi Manifesto, written by Martí and signed by him and Máximo Gómez on 25th March 1895, during their journey towards insurgent Cuba, where the Teacher intended to fully realise the revolutionary ideas to which he had devoted himself. Therefore, while preparing in campaign the Assembly – which death prevented him from reaching – that was to establish the appropriate leadership structure for the combatant homeland, he expressed that representation in said Assembly corresponded to «all the visible Cuban people,» that is – in the conditions of the country at war – to «the risen Cuban masses.»

They were groups representing the Cuban masses that rose up in different places on the Island on 24th February 1895, according to a novel and popular plan, whose maximum leader could not, on that date, be in any of those points: like the most outstanding leaders called to follow him, he had to remain abroad until after the start of the contest, for the sake of the security required by the movement he headed.

To all those groups of insurgents, and to the combatants who supported them, we owe the devotion they earned the right to with the new «snort of honour» where – at the voice and example of Martí – the dignity of Cuba was once again fully demonstrated, fertilising the path that would lead our people to victory. (Author: Luis Toledo Sande | internet@granma.cu)

-

Granma Archive. Published under the title Uprising in Cuba, in the print edition of 24th February 1988.