There are illustrious families. Those with true value are not those whose lineage and coffers mark their degree of celebrity, but rather those whose prestige comes from having contributed to the good of others, through their aims and devotions.

The one bearing the surnames Henríquez Ureña, born to the Dominicans Salomé Ureña, a Dominican educator and poet, one of the most distinguished authors of her country; and Doctor, writer and patriot Francisco Henríquez y Carvajal, counts among them. Fran (Francisco), Pedro, Max (Maximiliano) and Camila were the children of that marriage.

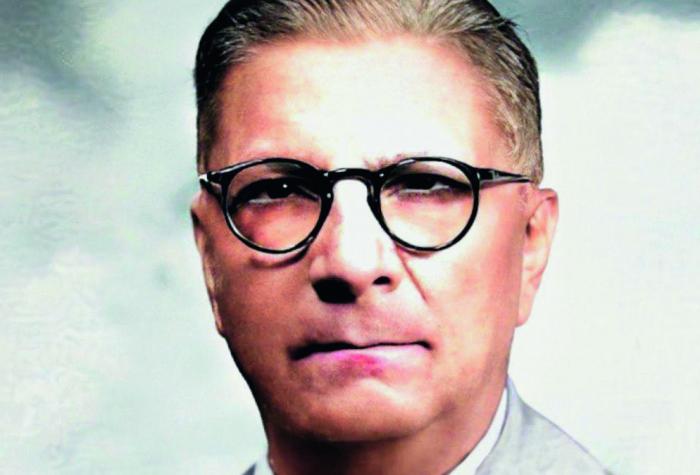

To Pedro, a distinguished humanist, we recently dedicated a few lines in these pages to remember him on the anniversary of his passing. Of Camila, an outstanding educator, Cuban by naturalisation, one must speak whenever the Cuban revolutionary process is mentioned, as she soon joined the formation of a new pedagogy and held important posts in the Ministry of Education, already possessing a prestigious record. We now address Max (16 November 1886 – 23 January 1968), also a notable personality who left his mark on Cuba, as 139 years have just passed since his birth.

Reading his biography in various sources informs us of his devotion, from a very young age, for reading and literary and cultural content in general, which was nourished by his travels to various countries and his education. In his own country, he graduated with a baccalaureate in Sciences and Letters, later studying in New York and earning a doctorate in Cuba, in Philosophy and Letters.

Santiago de Cuba, where he was a professor of Literature at the Normal School for Teachers, saw him found and direct the magazine Cuba Literaria. In Havana, he completed his law degree. He was a minister plenipotentiary in London and Washington and Superintendent General of Education. His erudition allowed him to join institutions such as the Cuban National Academy of Arts and Letters, the Dominican Academy of Language and the Mexican Academy of Language.

Max stood out as a notable orator, for which he was applauded in several Latin American countries, and also in the United States. He was an ambassador to Brazil and Buenos Aires and co-founder of the Dominican Academy of History, alongside his uncle Federico Henríquez y Carvajal. He taught at the Autonomous University of Santo Domingo and at the Pedro Henríquez Ureña National University.

In a book (Hermano y maestro) in which he aims to pay homage to the closest of his brothers, and which he wrote in Havana, he evokes his memories and, speaking of his dear Pedro, speaks of himself. The images of his mother and of Pedro, barely a year older than him, are among his most remote memories. «The world for me was concentrated in those two beings,» he affirmed.

He would have been five years old when Pedro, who sought to train him in numbers and diction, taught him to read. From then on, they accompanied each other in readings, which from childhood were concentrated preferentially on the works of Shakespeare. In their father, who was often absent from home due to his medical studies, the brothers found «a mentor of great authority,» and in Fran, a more experienced companion.

One afternoon, leaning out on the balcony, the children spoke of how interesting it would be to collect the works of all Dominican poets. «From that day on, scissors in hand, we set to work.» From magazines and newspapers, they then copied the verses of the poets of their land that they found. «The title I adopted and Pedro approved was: Poetas Dominicanos. Three thick volumes were the fruit of that endeavour,» he recounts.

«Pedro and I were not content with being novice makers of poetry collections: we wanted to have our own newspapers. I launched into circulation at home a small weekly handwritten sheet, with terrible handwriting and the occasional spelling mistake. I named it: La Tarde. Naturally, only one copy was published, which circulated through the house from hand to hand. Someone pointed out to me that the chosen name was more fitting for a daily newspaper that came out every afternoon, and so I changed it to Faro Literario. Pedro launched into circulation another small sheet (..), which he baptised La Patria, and in it appeared reproductions of our poets, with his commentaries, which were perhaps the first manifestation of his future gifts as a critic and essayist.»

With a grateful voice, Max – a modernist poet and author of some thirty titles, among which are Tablas cronológicas de la literatura cubana and Panorama histórico de la literatura cubana – writes this book which, even without intending to, also shows the reader his own greatness and that of an admirable lineage, which he served by helping others with his proven talent.